Hyponatremia, characterized by low sodium levels in the blood, presents a complex diagnostic and management challenge for healthcare professionals. This guide aims to equip physicians, nurses, and other practitioners with the knowledge and tools necessary to accurately diagnose, safely treat, and meticulously document hyponatremia cases. By emphasizing a systematic approach to diagnosis, evidence-based treatment strategies, and best practices for documentation, this guide will help improve patient outcomes, minimize risks, and ensure regulatory compliance. This resource emphasizes clarity, completeness, and accuracy in clinical documentation, safeguarding both practitioners and patients. For more on hyponatremia medical coding, see this helpful resource: medical coding details.

Hyponatremia Clinical Documentation: A Practical and Thorough Guide

Hyponatremia, or low blood sodium, demands a nuanced understanding due to its varied etiologies. Distinguishing the underlying cause is crucial for effective patient management. This guide provides a structured approach to accurately documenting hyponatremia cases, optimizing patient outcomes while mitigating potential risks.

Understanding Hyponatremia: Beyond the Numbers

Hyponatremia is defined as a serum sodium level below 135 mEq/L. While seemingly straightforward, its implications can be significant, ranging from mild neurological symptoms to severe complications like seizures and cerebral edema. The key challenge lies in recognizing that hyponatremia can arise from diverse conditions, including dehydration, euvolemia, and hypervolemia. Therefore, a comprehensive diagnostic and documentation strategy is paramount. Accurate identification and recording lead to appropriate interventions, minimizing potential complications such as cognitive impairment and seizures.

Diagnosing Hyponatremia: A Systematic Approach

Diagnosing hyponatremia requires a meticulous and systematic process, akin to solving a multifaceted puzzle.

Step 1: Thorough Assessment of Hydration Status: Determining the patient’s hydration status is the initial and fundamental step. Is the patient hypovolemic (dehydrated), euvolemic (normally hydrated), or hypervolemic (fluid overloaded)? Conduct a comprehensive physical examination, noting signs such as skin turgor, mucous membrane moisture, presence of edema, and jugular venous pressure. Obtain a detailed medical history, focusing on fluid intake, output, and any recent changes in weight. Accurate assessment of hydration status forms the foundation for subsequent diagnostic and therapeutic decisions.

Step 2: Comprehensive Laboratory Evaluation: Obtain a comprehensive set of laboratory tests to elucidate the underlying cause of hyponatremia. Key tests include:

- Serum Sodium: Essential for confirming the diagnosis and monitoring treatment response.

- Plasma Osmolality: Differentiates between true (hypo-osmolar) hyponatremia and pseudo-hyponatremia.

- Urine Osmolality: Aids in differentiating between renal and extra-renal causes of hyponatremia.

- Urine Sodium: Helps determine if the kidneys are appropriately conserving sodium.

- Additional Tests: Depending on the clinical context, consider measuring serum potassium, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, glucose, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

Meticulous documentation of laboratory findings, including dates, times, and units of measurement, is crucial for accurate interpretation.

Step 3: Integration of Clinical and Laboratory Data: Correlate the patient’s clinical presentation with the laboratory results to formulate a differential diagnosis. For example:

- Hypovolemic Hyponatremia: Characterized by low serum sodium, low plasma osmolality, high urine osmolality, and low urine sodium (if extra-renal losses) or high urine sodium (if renal losses, such as diuretic use).

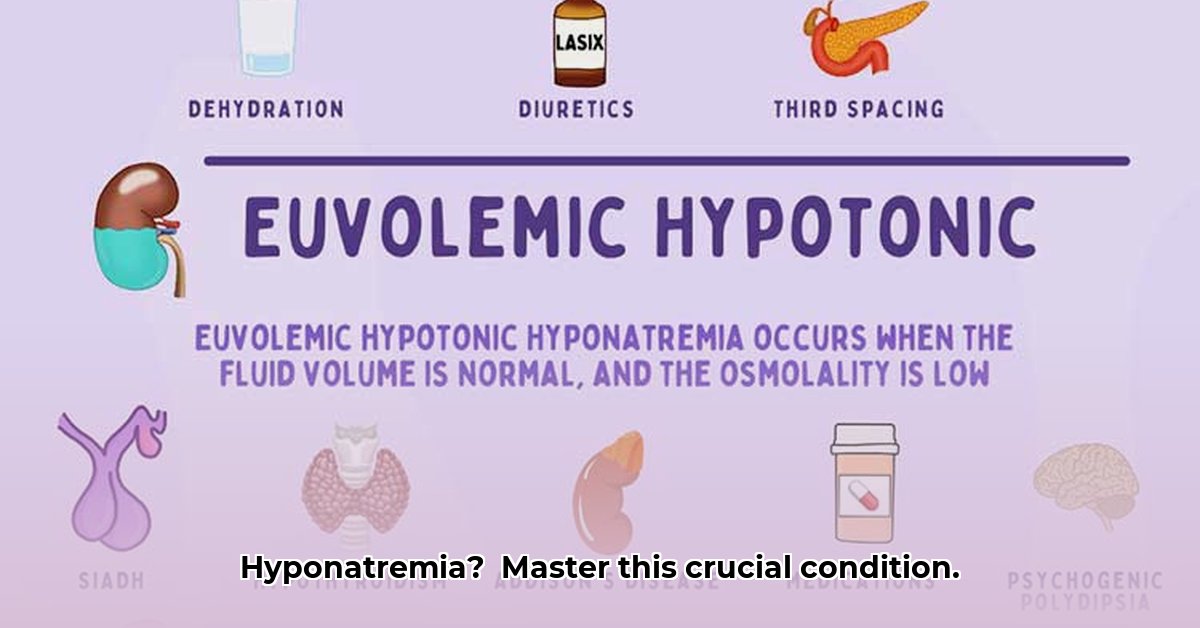

- Euvolemic Hyponatremia: Characterized by low serum sodium, low plasma osmolality, and variable urine osmolality and urine sodium. SIADH is a common cause.

- Hypervolemic Hyponatremia: Characterized by low serum sodium, low plasma osmolality, low urine osmolality, and variable urine sodium. Common in heart failure, cirrhosis, and nephrotic syndrome.

Precise data interpretation facilitates targeted investigation and management.

Step 4: Identification of the Underlying Etiology: Hyponatremia is often secondary to an underlying medical condition or medication. Consider the following potential causes:

- Medications: Diuretics (especially thiazides), antidepressants (SSRIs), and certain pain medications.

- Hormonal Imbalances: SIADH, adrenal insufficiency, and hypothyroidism.

- Renal Disorders: Chronic kidney disease and salt-wasting nephropathies.

- Cardiac Conditions: Heart failure.

- Hepatic Diseases: Cirrhosis.

- Gastrointestinal Losses: Vomiting, diarrhea, and nasogastric suctioning.

- Excessive Water Intake: Primary polydipsia and beer potomania.

Thorough investigation of potential underlying causes is paramount for effective long-term management.

Step 5: Comprehensive Documentation: Document all aspects of the diagnostic process meticulously, including:

- Patient’s presenting symptoms and medical history.

- Physical examination findings, with specific attention to hydration status.

- Laboratory results, including dates, times, and units of measurement.

- Interpretation of laboratory data and correlation with clinical findings.

- Differential diagnosis and justification for pursued investigations.

- Identified underlying cause of hyponatremia.

Comprehensive documentation ensures continuity of care, facilitates communication among healthcare providers, and provides a defensible record of clinical decision-making.

Treating Hyponatremia: A Balancing Act

Treating hyponatremia requires a delicate balance between correcting the sodium deficit and avoiding overly rapid correction, which can lead to osmotic demyelination syndrome (ODS). Treatment strategies must be individualized based on the severity and chronicity of hyponatremia, as well as the patient’s overall clinical status.

- Chronic Hyponatremia (Gradual Onset): Gradual correction is essential to minimize the risk of ODS. The recommended rate of correction is typically no more than 10 mEq/L in the first 24 hours and no more than 8 mEq/L per 24 hours thereafter. Frequent monitoring of serum sodium levels is crucial to guide treatment adjustments.

- Acute Hyponatremia (Sudden Onset): Acute hyponatremia, particularly when symptomatic, requires more urgent intervention. Hypertonic saline (3% NaCl) may be administered under close monitoring, with careful attention to the rate of correction. The goal is to alleviate symptoms and prevent neurological complications.

- Specific Treatment Modalities:

- Fluid Restriction: Often a mainstay of treatment for euvolemic and hypervolemic hyponatremia.

- Sodium Chloride Tablets: May be used to supplement sodium intake in patients with mild, chronic hyponatremia.

- Loop Diuretics: Can be used in conjunction with fluid restriction to promote sodium excretion in hypervolemic patients.

- Vasopressin Receptor Antagonists (Vaptans): May be considered in certain cases of euvolemic or hypervolemic hyponatremia, but their use requires careful monitoring due to potential side effects.

Areas of Uncertainty: Navigating Expert Disagreement

Despite established guidelines, some aspects of hyponatremia management remain subject to debate. For instance, the optimal diagnostic criteria for SIADH continue to evolve with ongoing research. Similarly, the precise number of low sodium readings required to definitively diagnose hyponatremia may vary based on clinical context and individual patient factors. Staying abreast of current literature and engaging in continuous professional development are essential for navigating these areas of uncertainty.

Best Practices for Hyponatremia Documentation: A Comprehensive Checklist

- Serial Serum Sodium Levels: Document all serum sodium levels, including dates, times, and laboratory values.

- Detailed Hydration Status: Clearly describe the patient’s hydration status based on physical examination and clinical assessment.

- Complete Laboratory Data: Include all relevant laboratory results, such as plasma and urine osmolality, urine sodium levels, and other pertinent biochemical markers.

- Underlying Medical Conditions: Thoroughly document any underlying medical conditions that may be contributing to hyponatremia.

- Medication History: List all medications the patient is currently taking, with specific attention to those known to cause or exacerbate hyponatremia.

- Treatment Plan and Rationale: Clearly articulate the chosen treatment plan and the rationale behind it, including specific goals for sodium correction.

- Patient Response to Treatment: Monitor and document the patient’s response to treatment, including changes in serum sodium levels and resolution of symptoms.

- Potential Side Effects: Document any potential side effects of treatment, such as overly rapid correction or adverse drug reactions.

- Accurate Coding: Utilize appropriate diagnostic and procedural codes for billing and record-keeping purposes.

Optimizing Electronic Health Record (EHR) Utilization

EHRs can be valuable tools for managing hyponatremia, but effective utilization is essential.

- Standardized Terminology: Use clear and concise language, adhering to standardized medical terminology.

- Alerts and Reminders: Configure EHR alerts to flag low sodium readings and prompt clinicians to order appropriate investigations.

- Structured Data Entry: Utilize structured data entry fields whenever possible to minimize errors and facilitate data analysis.

- Accurate Coding and Billing: Ensure accurate coding and billing practices to avoid claim denials and regulatory scrutiny.

Key Laboratory Findings in Hyponatremia: A Quick Reference Guide

| Hyponatremia Type | Plasma Osmolality | Urine Osmolality | Urine Sodium |

| ———————– | ——————– | ——————–

- Best Books on Meditation Recommended by Mindfulness Experts - January 30, 2026

- Best Mindfulness Books for Anxiety, Sleep, and Daily Peace - January 29, 2026

- Books On Mindfulness For A Happier, More Present Life - January 28, 2026